It's amazing how fragile good practices are

Enabling effective intervention implementation

By Dr. Amanda VanDerHeyden, SpringMath author, policy adviser, thought leader, and researcher

The biggest theme in implementation science is that most people, even when trained, well-supported, and fully equipped, do not implement academic intervention well, which caused our colleague, Dr. Ronnie Detrich, to remark profoundly, “It’s amazing how fragile good practices are.”

In fact, implementation data are dismal, suggesting that fewer than 12% of teachers in well-controlled studies in the peer-reviewed literature actually implemented the intervention as planned beyond 1-2 sessions (Mortenson & Witt, 1998; Noell & Witt, 2000; Noell et al., 2002; Wickstrom et al., 1998; Witt et al., 1997). The most common reason for failed interventions has nothing to do with whether the intervention could have been effective; rather, most interventions fail because they are not consistently used in a sufficient way to bring about the desired learning improvements.

The prevalence of poor implementation should not be surprising when you think about human behavior in general. If you are expecting teachers to implement well (or if you are a teacher expecting yourself to implement well), you are really expecting teachers to be super-human or to defy the laws of human behavior.

Consider that many of us have recently made New Year’s resolutions. A quick online search reveals that many polls over the last few years suggest nearly all adults abandon their resolutions well before mid-February. I would be willing to gamble that resolutions are actually abandoned much sooner if we really tracked implementation behavior (as opposed to self-reported behavior) in poll responses.

|

Fortunately, directly tracking implementation of math interventions has been done in our field indicating approximately 12% of teachers continued implementation beyond the first couple of sessions. Importantly, asking teachers if they will implement or even if they are implementing, is usually not consistent with measuring their implementation directly. This is not an indictment of teachers; rather, this is human nature. In psychology, most researchers understand that self-appraisals or self-reports of specific behaviors are often highly unreliable. You may feel skeptical of such dismal views of intervention implementation. You might recall one or two teachers who faithfully follow through on all requests in the classroom. But again, well-controlled research studies find that actual implementation persists beyond the first few sessions for only about 12% of teachers. Further, most of the variables you might imagine like lacking the skills, the materials, or even low acceptability of an intervention as possibly causing poor implementation were controlled for in the studies listed above. In other words, about 12% of teachers can be expected to sustain implementation beyond one or two sessions under a best-case scenario. |

Implementation is the one place to be cynical in your views as a leader and coach, and even for yourself as a classroom teacher. Assuming implementation is occurring is a foolhardy assumption. In effect, assuming that most teachers will implement well believes that all teachers fall into the 12% category. Stated another way, your assumption of strong implementation will be wrong about 88% of the time. The fact that 12% of teachers do implement academic interventions well, in my opinion, probably is superior to many other areas of human behavior — because teachers genuinely care about their students and want to do the things that benefit their students. Thus, I suggest you assume that implementation will not be sustained without support from the system. I further suggest that light-touch superficial strategies, such as allowing teachers to select the intervention and providing all needed materials for the teacher to use, will not be effective at ensuring strong implementation (Sterling-Turner & Watson, 2002). As a rule, interventions that are less complex require fewer adults to implement, provide all needed materials, and provide up-front training for implementation are effective antecedent support strategies that will at least take you to 12% correct implementation. |

Yet, we do know what works to improve implementation. Implementation behavior is behavior after all, behavior conducted by adults in classrooms. We can support adult behavior like we support all behavior — using antecedent and consequence strategies. Antecedent strategies that produce some effect (get you to 12% implementation) include things like offering a choice of intervention, making sure the teacher agrees to conduct the intervention, equipping the teacher with all needed materials to implement the intervention, and training the teacher to do the steps of the intervention with a “script.” These actions should be considered necessary but not sufficient if your goal is to ensure effective implementation of specific tactics in classrooms. In contrast, performance feedback is a consequence strategy that produces a rather whopping effect size on implementation, taking implementation from 12% to above 80% implementation in well-controlled studies (Noell, et al., 2005).

Here are a few highlights from the outstanding randomized controlled trial directed by Noell and colleagues (2005):

-

About 45 student-teacher dyads were randomly assigned to three experimental conditions: weekly follow-up (as typically would happen in schools meaning informal or formal checking in outside of the classroom setting and asking the teacher how things are going), commitment emphasis (weekly meeting with a script to get the teacher to verbally recommit to the intervention each week), and performance feedback.

-

There was a strong effect size for performance feedback on implementation integrity (effect size = .81). Treatment integrity was correlated with improved student outcomes (resulting from the intervention) in the performance feedback condition only.

-

Teachers rated the interventions as acceptable, their implementation as very high, and intervention effects as strong across all three conditions (when in reality, only the performance feedback condition produced strong integrity and student performance improvements).

What is performance feedback?

Performance feedback involves a. knowing whether the intervention is being used each day or week via direct measurement of implementation, and b. a leader or colleague showing up weekly to review use of the intervention and the gains produced by the intervention that week for the students in collaboration with the adult directly responsible for the intervention. The tone of performance feedback is collegial and supportive. The coach or principal asks, “How can I help? What went wrong? Let me watch today and see how I can help.” It does not involve conversations around conference tables where teams speculate about causes of weak intervention effects as nearly always such discussions lead to incorrectly indicting the intervention when the intervention was not the problem.

|

Being equipped with an understanding of implementation science in academic intervention, savvy leaders and frontline implementers can work within the natural expected constraints of implementation behavior. In other words, teams can understand that they must actively plan for effective implementation and use performance feedback to sustain effective implementation over time. Intervention implementation research is an area of exciting discovery and future innovations may allow for easier ways of ensuring optimal implementation (we are involved in this work ourselves). For example, finding academic interventions that produce the entire effect within the constraints of typical implementation behavior (e.g., within only one or two sessions) would be an effective solution. In fact, this tactic has been used in medicine with single-dose medications which have better fidelity than medications that require more doses for more days. This particular innovation is not available in academic intervention; yet other clever ways of supporting implementation can be devised via research and much of this science has been built into SpringMath — automated decision making and behind-the-scenes adjustments to rules when systems make certain implementation decisions that reduce the accuracy of the rules or attenuate the intervention effects. |

The most surefire way to ensure implementation is to plan for weekly performance feedback delivered with graphs of use and student performance gains (Mortenson & Witt, 1998; Noell et al., 2002), which SpringMath has been built to help you do. The integrity metrics that drive specific support recommendations in your coach dashboard have been tested in a randomized controlled trial of classwide math intervention finding that they outperformed direct observation in the classroom and predicted student gains in intervention (VanDerHeyden et al., 2012). You can feel confident about using your coach dashboard to tell you where intervention implementation needs support. And you must do the human part, that is, use these supports to initiate, sustain, and course correct on unsuccessful implementation. SpringMath is designed to make correct, successful, complete implementation more likely among our colleagues who choose to allocate their precious time and instructional resources to implementing SpringMath to raise achievement. Be sure to check out chapter 7 of Supporting Math MTSS Through SpringMath to see how SpringMath directly measures implementation and student learning gains, and access actionable advice about how to implement math MTSS. |

Regardless of the attention to implementation success in the up-front design and ongoing development and management of SpringMath, we cannot overcome this universal truth: without consistent teacher behavior change, no intervention tool can work as intended. If you have chosen tools wisely (considered costs to implement and your capacity to support implementation), then the singular burning task in front of you is to implement better.

Advice and resources to get going, restart, or sustain SpringMath

Note that we say "begin." Implementation support is never done. Even veteran teachers and systems with excellent implementation in prior years will predictably drift over time. Access resources for ongoing implementation support in our implementation rubric. While no curriculum, product, tool, or intervention will automatically deliver results without direct, hands-on implementation support, SpringMath is designed to help you do this.

Your coach dashboard is your command central for managing school- and grade-level support for implementation. As a teacher, your dashboard is command central for conducting the actions you need to conduct in the classroom to enable the intervention to work with your students. As a coach, your week should begin with logging in to your SpringMath account to access the coach dashboard. MTSS is complex in implementation but simple in ingredients — you are screening all students fall, winter, and spring, and starting classwide intervention where recommended. Eventually you are conducting the brief diagnostic assessment and implementing the recommended individual interventions.

Each week on your "school overview" tab, you can see if teachers have entered a score from classwide intervention for the week. If a teacher has not entered a score from the preceding week, that teacher goes on your list for a quick check-in this week. Next, you can see rate of skill mastery within and across classrooms. Any class that is lagging behind other classes at the same grade level should go on your list for a visit this week. Any grade that is lagging behind other grades should also go on your list for some in-class troubleshooting this week.

You can also see average weeks to mastery across skills by teacher. You'll want to see all teachers moving along from skill to skill two or three weeks per skill, on average. If you notice greater than two weeks per skill, you should tab through that teacher's classwide intervention graphs to confirm most students are improving week over week and the teacher is using all recommended actions. If we recommend a boost-it activity, you can check to see that the teacher is using the boost-it activities each day. Check this directly by clicking on "boost-it" and seeing that the teacher is on the expected day of materials. If the teacher is on "day 1," the teacher has not used these activities. Helping the teacher to use the boost-it activity will accelerate growth for students in that classroom.

Finally, you can pay attention to the number of students being recommended for individual intervention in classrooms. There is a dosage benefit to the accuracy with which we recommend students for individual interventions. While SpringMath does not miss kids for individual intervention, it may over-identify students for intervention when classwide intervention implementation is weaker.

As a leader, you are right to emphasize strong implementation of classwide intervention as your highest priority as it will make your entire MTSS system more efficient — and more effective. If you follow the "scores increasing" metric this will track closely with the number of students recommended for individual intervention and we suggest you aim for better than 80% on this value. If this value is not 80% or higher, click on that teacher's name and view classwide intervention progress. You are looking for consistent upward growth for all students. If you don't see consistent upward growth for all students, then that teacher goes on your list for a visit.

Be sure your visit uses the active ingredients of performance feedback, which means that you need to show up when the intervention is scheduled to occur, watch the intervention, and try to be of help to the teacher. Having a conversation with the teacher outside of the classroom is not likely to translate to improved intervention success in the classroom (Stokes & Baer, 1977).

To access resources to help teachers when you visit the classrooms, use the resource links in the implementation rubric. Your goal as a coach is simple: you want the teacher to take all recommended actions from within the teacher dashboard in a high-quality way and you want to see that when the teacher does so, students grow.

Understanding that you don't have to speculate about student progress is powerful. It also helps you avoid wasting resources that won't improve your implementation or the results. Any ideas about why desired progress is not occurring can be directly tested, usually right inside the coach and teacher dashboards. What you cannot see or test in the dashboard, you can see and test by watching the actual intervention.

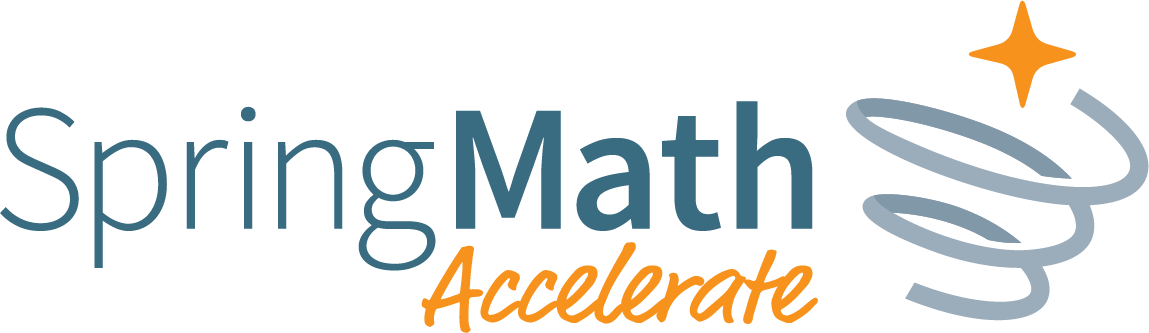

Your coach dashboard will show you the classes that are lagging and more classes should be experiencing success than not. You should see scores entered every week, score consistency above 80%, and average weeks to mastery at or below two weeks. Most importantly, when you tab through a teacher's graphs you should see graphs that look like the one below from a second-year school of about 550 K-4 students. The district started both their elementary and middle school in year one with onboarding and ongoing coaching support provided by our team. They also reached out to other districts in their state to access a community of support for their implementation.

In a strong implementation, classes at each grade level should have strong upward growth for nearly all students, meet the mid-year goal for skill mastery in classwide intervention, show very few missing scores, and show faster mastery of more complex skills like multi-digit addition (the class featured here mastered all subsequent multi-digit addition and subtraction skills within a couple weeks).

In your weekly work with teachers, you can share examples of effective implementation directly with your teams to encourage and inspire all teachers to implement consistently.

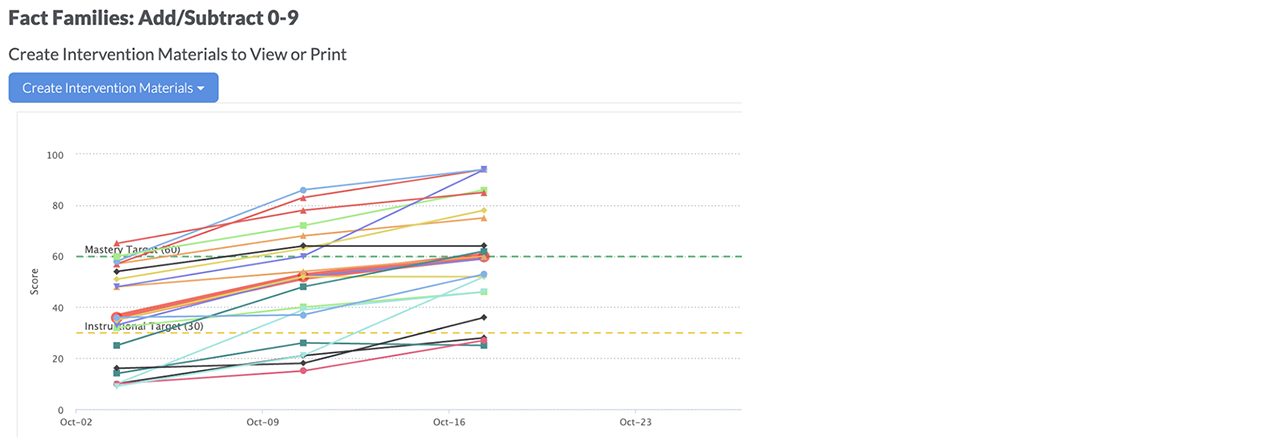

In the “growth” tab, you should also see that the percent of students meeting the instructional target in the final classwide intervention session (brown bars) is much greater than the percent meeting the instructional target at screening (yellow bars).

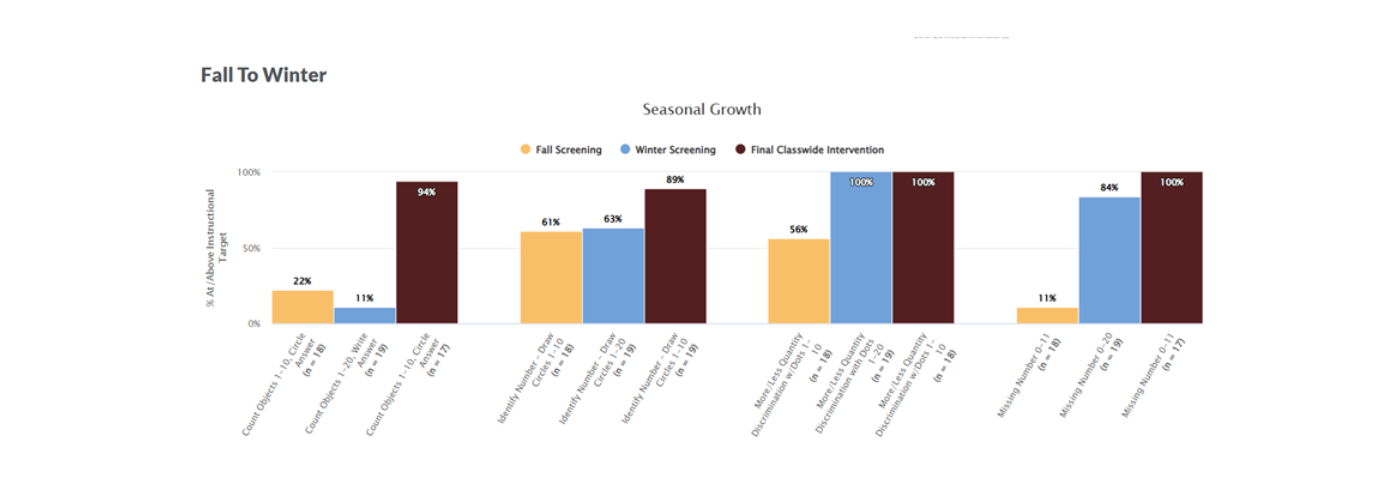

You should be able to click on “individual student skill progress” and see that very few students remain in the red range (frustrational) in the final classwide intervention session. In the next example below, you can expect that students 1, 6, and 16 have been recommended for individual intervention with students 1 and 6 being assigned top priority to start individual intervention.

The principal is deeply committed and involved in the implementation

MTSS works because it positions student achievement as a predictable result of effective instruction and then it uses the structures of screening, progress monitoring, and data-based decision making to continually aim at the target of delivering more effective instruction. The role of the principal is to know where instruction can be improved and to make that happen consistently through effective support of classroom teachers.

Leading MTSS requires technical mastery of the daily actions of MTSS, including:

-

Assessing but not over-assessing

-

Removing structural barriers to effective instruction

-

Evaluating the effects of instruction in real time

-

Intensifying instructional opportunities where needed

But leading MTSS also requires adaptive leadership capacity to:

-

Troubleshoot with faculty

-

Motivate faculty to try instruction differently

-

Build trust with faculty that you will show up to help them be successful with their students.

SpringMath is highly effective when principals log in weekly and use the coach dashboard to guide their math MTSS implementation schoolwide (VanDerHeyden et al., 2012).

Use your program evaluation

One of the best things you can do to refine, sustain, or re-start your implementation is to use your annual program evaluation. Program evaluation is right under your log-in ID in the right-hand corner of your screen in your coach dashboard.

Within your program evaluation, you will find everything you need to evaluate how well you implemented and what results you got on a variety of outcome measures, as well as ideas to implement better in the following year. You will also find a report of gains in student proficiency by actual dosage of implementation by grade level in your school. These data are a powerful way to help teachers see that when they implement well, they will produce greater math mastery for their students. Seeing this growth is powerful and necessary feedback for your teachers that helps reinforce their implementation behavior.

References

Mortenson, B. P., & Witt, J. C. (1998). The use of weekly performance feedback to increase teacher implementation of a prereferral academic intervention. School Psychology Review, 27, 613–627.

Noell, G. H., & Witt, J. C. (2000). Increasing intervention implementation in general education following consultation: A comparison of two follow-up strategies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(3), 271.

Noell, G. H., Duhon, G. J., Gatti, S. L., & Connell, J. E. (2002). Consultation, follow-up, and behavior management intervention implementation in general education. School Psychology Review, 31, 217-234.

Noell, G. H., Witt, J. C., Slider, N. J., Connell, J. E., Gatti, S. L., Williams, K. L., Koenig, J. L., Resetar, J. L., & Duhon, G. J. (2005). Treatment implementation following behavioral consultation in schools: A comparison of three follow-up strategies. School Psychology Review, 34, 87-106.

Sterling-Turner, H. E., Watson, T. S., & Moore, J. W. (2002). The effects of direct training and treatment integrity on treatment outcomes in school consultation. School Psychology Quarterly, 17(1), 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.17.1.47.19906

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 349-367.

Wickstrom, K. F., Jones, K. M., LaFleur, L. H., & Witt, J. C. (1998). An analysis of treatment integrity in school-based behavioral consultation. School Psychology Quarterly, 13, 141-154.

Witt, J. C., Noell, G. H., LaFleur, L. H., & Mortenson, B. P. (1997). Teacher use of interventions in general education settings: Measurement and analysis of the independent variable. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30, 693-696.